Drawings

« Memory is a space drawn in two »

There are areas of memory where bubbles of shadow can swell. They take on the appearance of grayed pearls. They risk enchanting us while lulling us into that sweet seduction that the historian Marc Bloch called the lethal illusion of an eternal present.

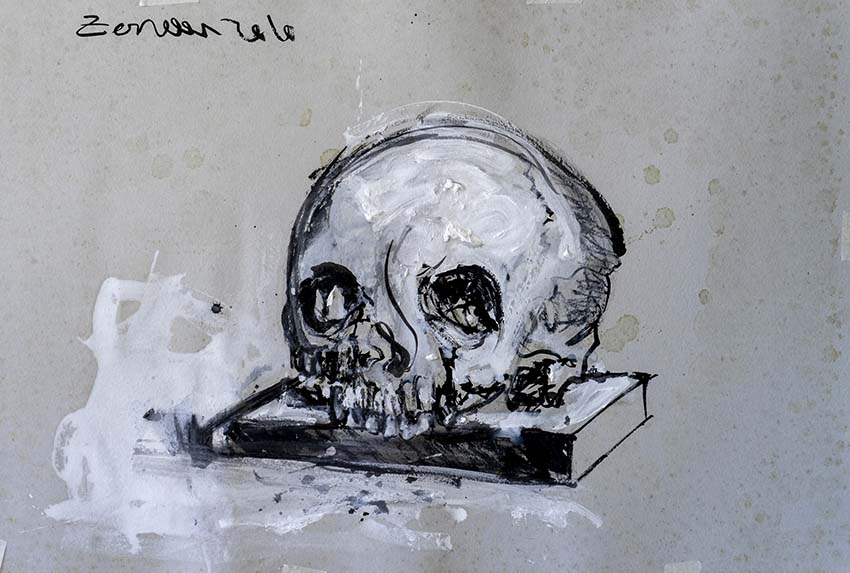

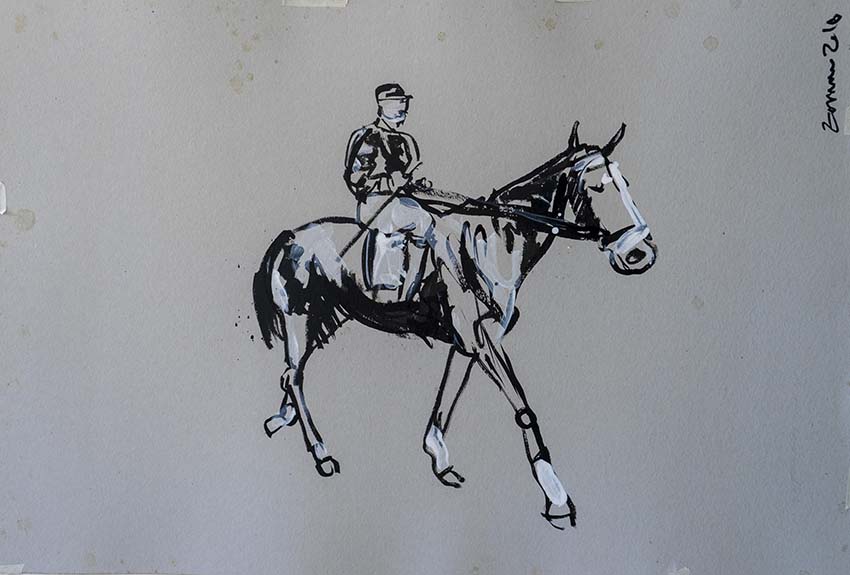

The work that the young artist Abdelaziz Zerrou presents to us today on the occasion of his solo exhibition seems to push the perspectives of our imagination to the point of forcing us to blow on all those bubbles and to open our eyes to a past that, if unseen, continues to be present.

When Abdelaziz asked me to work on a text that would provide a coherent historical and social framework to his work, from my house on the Adriatic Sea I began studying his drawings, squinting at those images that, unfamiliar, insisted on telling me something that, though from afar, deeply concerned me.

The images that Abdelaziz presents today depict scenes of a past distant to me in time, but especially in space. They tell stories of colonialism, of resistance, stories of supremacy and struggles against that supremacy, particularly against that perpetrated by the French government. Stories of reclamation, where what is being claimed is the right to be human beings in the face of those who believe they can nullify you after having taken from your hands the space and legitimacy over that space.

Stories that have been repeating since the dawn of time, but never in the same way. Just as the way an artist tries to tell them is never the same. And so I, despite being so distant, so different, yet in those lines, in that warmth, in the movement that returns differently on the pencil than on the print, from those images I feel the revival of a thought that somehow belongs to me and rekindles, perhaps precisely by virtue of that particular technique with which Abdelaziz has created his works: mostly India ink and gunpowder.

But how can it be, I wonder, as I continue to observe his drawings and persist in following the path of a research that inevitably slips into literature, towards my world, my formation; eyelashes brushing the shelves of my imagination, of what is the face of my memory, and inevitably words that I have read and reread are drawn in my head. Those of the writer José Saramago, who coincidentally with Abdelaziz shares the mobile and clear space of the Mediterranean Sea.

Saramago wrote in those notebooks drafted in the solitude of Lanzarote about memory: ‘We change position, we turn our head to one side, we try, through successive juxtapositions or lateralizations of points of view, to recompose an image that we can recognize as still ours, linking it with this one we have today, already almost of yesterday.’ Thus, Abdelaziz’s images are not a slavish reproduction of those illustrations that were made in history, but they reverse the perspective, showing the symmetrical and specular version, « As if he wanted, with his work, to return to the original image—the one that existed before finding itself in black and white within the photographic mirror of historical illustrations.

Then Marc Bloch’s words come back to me again. This is what history is for: to make us go back, to discover the faces, the shadows, the real version of that history that has always been told to us in systems, forgetting about the people. And what language better than art can force us to do it without getting lost, to dissolve those bubbles of fog and finally transform them into knowledge? Thus, in Abdelaziz’s images, I seem to find those very people again, while we can distinguish his work as an artist from that of a simple historian, because he not only brings us back into that history but manages to paint a new face onto our memory.

So, at this point, what remains for us is to try to find the answer to an ancient question: what is memory, if we exclude that archetypal and unconvincing space with which they have fooled our minds? How can Abdelaziz and I—I on one side, he on the other—find ourselves in that same space of memory, as if it belonged to both of us, yet I am so distant and he with a history inevitably different from mine?

Recently, from this distant Italy from which I write to you, we lost someone many have described as the poet-psychiatrist Massimo Fagioli. He distinguished human beings from animals because humans, if they are truly human, never lose memory but preserve it in some hidden area of themselves—a privileged space that doesn’t sleep but becomes visible in dreams or in the images that artists give us during the day.

Artists like Abdelaziz Zerrou, artists who give us a new sense of history—a memory that becomes alive within a space drawn in two; he who brings it back to life, I who find myself alive in rediscovering it, while it forces me to lose something old, like a glass mask that falls and had made us strangers within the same sea: the lethal seduction of prejudice, the same that drags many towards the mortal illusion of the present from which we started.

Because this is what art does—the true, the authentic, the laborious and pure art: it forces us to return to the rough zones of history to unsettle us and prevent us from dying while we are still alive.

Ilaria Paluzzi

Text translated from Italian to English